Thursday, December 13, 2012

My larger version:

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Scientists at Idaho State University have mapped a previously unknown and active seismic fault in the northern Rockies capable of unleashing an earthquake with a magnitude as high as 7.5....I visited the fault scarp from the 1983 Mount Borah earthquake this summer (another illustration here). With nearly ten feet of vertical displacement in places, it's quite impressive. The mountains rose six inches while the valley floor dropped nine feet. We run a rapid on the Middle Fork of the Salmon whose main obstacle is a boulder dislodged from the cliffs by the quake 70 miles away. East-central Idaho is shaky country. Quakes here would be a big deal if the area weren't so sparsely populated.

....Glenn Thackray, chairman of the university's geosciences department, said the 40-mile-long fracture in the Earth's crust at the base of the Sawtooth Mountains near the tiny mountain town of Stanley is cause for some concern.

"There's a chance in the next few decades there will be an earthquake on this fault, and if it does happen it will be a rather large earthquake," he said.

Scientists located the fault with a remote sensing technique that relies on laser-equipped airplanes. They were able to gather data about its history by analyzing sediment cores lifted from Redfish Lake, a mountain lake on the fault line famous for its historic sockeye salmon runs.

Thackray said researchers believe the fault triggered two earthquakes over the past 10,000 years, one some 7,000 years ago and another 4,000 years ago, suggesting significant seismic activity occurs at the site every several thousand years.

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

This Highway Adopted by The Yahweh 666 Warning Assembly

It was up the road. Also:

Police have arrested a 74-year-old woman who is accused of repeatedly dumping maple syrup, corn syrup, ketchup and mayonnaise into a library book drop in Idaho's capital city... [She] was a person of interest in at least 10 other condiment-related incidents

Source.

Friday, September 25, 2009

If anyone wondered what (besides sloth) was consuming my blogging output lately, here's your answer: researching Turkey, making the agonizing decision as to just where to go: the place is just crawling with worthy destinations. It's as big as Texas, but oh! so much more fascinating. And I've been studying Turkish,a very laudable tongue, barbaric and yet refined in its intricacy. I really enjoy non-Indo_European languages. The lack of grammatical gender alone makes them greatly superior, and what bliss is Turkish or Finnish regularity, where rules apply consistently enough to be worth remembering.

With any luck, I'll be much more interesting in a couple weeks. Here's a shot from the Selway this summer to tide you over:

Friday, July 17, 2009

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Yep, I'm a proud member of the Cartographic Thought Police.

Friday, August 03, 2007

A scenic, also from the Middle Fork:

Finally, a shot which begins to convey a faint idea of the most dramatic sandstone erosion I've ever seen. The location is in northeastern Utah, and doesn't need extra publicity. The genuinely interested can no doubt sniff it out on their own.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

The folks at Querencia are always blogging rock art, so I was inspired to do the same when I found a couple long-forgotten photos in an old trunk. These pictographs represent a very obscure tribe, the Sheepeater Shoshone of central Idaho (also sometimes called the Tukudeka). Both of these small panels are found near the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, one of the deepest and wildest river canyons in the nation. They are probably painted with iron oxide pigment mixed with animal fat and blood. The bird and bighorn (below) seem clear enough, and the well-endowed gentleman is a common enough theme in the area. One excellent panel, unfortunately not shown here, is called by names which vary according to rafting company: Shark Fin, for the prudes, after a distinctive boulder in the river nearby; One-Hung-Low by my compatriots; Big Chief Long-Dong by the unapologetic.

There are plenty of things to say about the Sheepeaters. They were a Numic-speaking people (like other Shoshone, Paiutes, Bannock, Goshutes and Utes). Beginning around the 15th Century, the Numic speakers spread from somewhere around Southern California to fill Nevada, Utah, the southern half of Idaho, western Wyoming and western Colorado. These tribes shared closely-related languages and common lifestyles of hunting-gathering and seasonal migration up into historic times.

Dagger Falls: some rock art is present here, though very deteriorated. Salmon can still be observed leaping up the falls in season, and the fishing here must have been excellent in Sheepeater times.

The effects of the European arrival were felt in the American West long before any actual Europeans showed up. Most notably, the Spanish brought horses into New Mexico, which soon escaped and went feral, and were gathered or stolen by the locals and traded northward. By the late 1700s, they'd made it to the Northern Rockies, and local lifestyles changed dramatically as a result. Tribes such as the Nez Perce, the Shoshone and the Utes were suddenly able to cover distance and carry a lot; they therefore began making seasonal expeditions east to the plains to hunt buffalo. The Plains Tribes responded by raiding them (particularly the Blackfeet, who got guns from Canadian fur traders ahead of everyone else). These tribes from the western slopes of the Rockies thereby acquired many accoutrements of Plains culture, such as feathered headdresses and tipis (which they could now transport), and became generally more nomadic and combative of necessity.

These changes took root very near the Sheepeater country. In the Lehmi Valley, around the present-day town of Salmon, Idaho, the Lemhi Shoshone bred horses and made the short hop over the Continental Divide to chase buffalo. Every halfway educated American is dimly aware of this, for it was one such hunting expedition that got Sacajawea captured by Mandan and taken to North Dakota; and it was successful Lemhi horse breeding that allowed her brother Cameahwait to give some animals to Lewis and Clark in 1804.

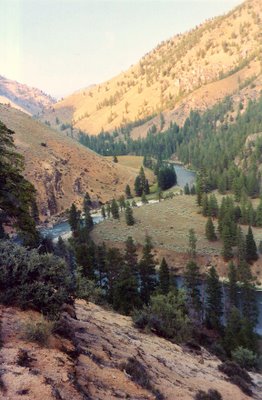

The Middle Fork country from high up: a small piece of river is visible lower right. The pink flowers are Bitterroots, endemic to eastern Idaho and western Montana, and an important food for local tribes.

While their Shoshone relatives in the broad valleys and plains of southern Idaho and Wyoming went along with this flow, the Idaho Sheepeaters are fascinating because they ignored these developments. Unlike the Lemhi Valley, Central Idaho just to the west is not good horse country; the Salmon River Mountains are a dense, incoherent knot of rugged peaks and very deep canyons. Furthermore, neither the river system nor the tribe was named at random: the biannual salmon migrations and the prolific bighorn sheep populations provided abundant resources for the Tukudeka. Though they continued their short seasonal migrations from high-elevation hunting grounds to low winter settlements, the Sheepeaters continued to winter in Northwestern-style pit-houses (there are many visible collections of house-pits on the Middle Fork), catch salmon and hunt sheep.

Typical river terraces where the Sheepeaters would build their house-pits. These were winter quarters with good exposures to sun and fairly low elevation. Much of the Middle Fork flows through a semi-desert environment, due to rain shadow effects of the surrounding mountains.

The few ethnographers who were aware of them at all long assumed that the Sheepeaters were degenerate hillbilly Shoshones, living a benighted existence in the mountains and evidently unable to find anything better to do. In fact, the Sheepeaters were known for excellent quality hides; they tanned one sheep's hide with two sheeps' brains, producing a valuable item that was traded for foreign commodities (notably obsidian; stone from both Yellowstone and the Cascades has been found in the area), and not a mark of abject poverty. Furthermore, there is no record of the Sheepeters eating grasshoppers, common practice among the Plains Shoshone and Bannock. Eating salmon instead of bugs is usually a sign that one is fairly well-off.

Sadly, the Indian Wars of the 1870s did not bypass this small and out-of-the-way tribe. 1876 was the year of the Little Big Horn; '77 saw the Nez Perce War; '78 the Bannock War in southern Idaho and eastern Oregon. In 1879, the Sheepeaters were one of the last unfought tribes in the Northwest. Unknown assailants killed a family of settlers near the South Fork of the Salmon, and some Chinese miners were murdered on the Yankee Fork, almost certainly by whites. It was easy to blame the Indians, and the merchants in Boise agitated for war. One wrote unabashadly in 1878 of eastern Oregon's "good fortune to have an Indian war and the concomitant shower of greenbacks all to itself."

Rough country for infantry: the army traversed a lot of this terrain, with mules, supplies and small artillery.

Two army columns were sent into the Salmon River Mountains, one from the south and one from the east. Their journals tell a rather farcical story of ten-foot-deep snowdrifts, blazing sun in the canyons, rattlesnakes, mules frequently tumbling down the slopes, but nary a sign of an Indian. Central Idaho is convoluted country, and the army was out of its depth. When one column at last met resistance on the slopes above Big Creek, the lieutenant promptly distinguished himself by hiding behind a tree. The soldiers were pinned down for over 36 hours and resorted to drinking vinegar (the site is named Vinegar Hill); the sound of Big Creek's cascades below must have been irritating in the extreme.

The Middle Fork near the confluence with Big Creek. The false summits in the photo are nowhere close to the top of the canyon, which rises 7,000 vertical feet in five horizontal miles from river to summits in this area.

At last, the army got lucky and captured a small group of women and children, along with one man, a Bannock refugee from the previous year's war. Desperate at this point to save face by returning from the mountains with a vaguely respectable number of Sheepeaters in tow, the lieutenant cut a deal with the Bannock. He led them to a Sheepeater camp, they rounded up the Indians and marched in dubious glory to Fort Hall in southeastern Idaho, still a Shoban (Shoshone-Bannock) reservation today.

There were undoubtably Sheepeaters remaining in the mountains after that summer, but the loss of even a small group was surely a major blow to so small and isolated a tribe. As we have seen above, they did rely at least somewhat on trade for their living, and there were no longer any free tribes nearby to trade with. What's more, central Idaho was declared open, and miners poured in. There is no direct record of what happened to the remaining Sheepeaters, but it seems safe to assume that they gradually headed south to the reservations. There they intermingled with plains Shoshone, Bannock and Northern Paiutes, and all intimate knowledge of the West's most isolated people, the tribe least changed by horses and guns, was lost.

The army named the lower reaches of the Middle Fork 'Impassible Canyon', but Shoshone pictographs are particularly abundant in these mazes of cliffs.

Source: The only book I know with a significant amount to say about the Sheepeaters is The Middle Fork: A Guide by Cort Conley. It includes extensive and often quite amusing excerpts from the soldiers' journals in the Sheepeater War. The Wikipedia entry on the Sheepeater War is laughably ill-informed. Particularly risible is this: "Sheepeater raiding party of ten to fifteen Indians attacked the troops as they rode on a train at Soldier Bar on Big Creek." The author is clearly thinking of a locomotive, but the only trains ever to have entered the Salmon River Mountains are equine, thank God!

(Final remark: the cohabitation of this post with Odious' charming tipi photograph is purest coincidence.)

All photographs are my own.

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

I recently stumbled across the above photograph, an image I remember well (not exactly fondly) from five-and-a-half years ago. It's a picture of the 2000 fires in the Bitterroot Valley, specifically the East Fork of the Bitterroot outside Conner, Montana. I was quite nearby at the time, in Salmon, Idaho, about an hour's drive south. It was the first time I was in the vicinity of major forest fires. I remember the smoke clouds to the west being so thick that we could look directly at the sun, sometimes seeing sunspots with our naked eyes through the perfect brown filter.

I've since floated and driven through several other small to medium fires. Though I was never in a scene as hellish as that photo, active blazes do put one in mind of scenes a few circles down in Inferno. The light is veiled and ruddy, the air unwholesome. Blackened silhouettes of trunks and stumps stand naked, carved into Rococo shapes by burning, some smoking like chimneys. Smoke pours from holes in the earth and stones tumble down the loosened slopes. Flames ripple up brushy hillsides or crackle into crowns of trees. I floated through one such on the Main Salmon in 2003 without incident. It seemed that we had come through after the worst was over, as the fire was calming down. But the next morning we awoke to strong winds, and looked back upstream to see an immense column of yellow-orange erupting into the sky above the canyon.

Whenever I have seen such fires in action, I have assumed the worst about what would be left when the flames were gone. But every time I have been pleasantly surprised. Where there's smoke there's fire, but there's usually vastly more smoke. The areas you see marked as burned in newspaper maps are very far from wastelands. Some patches are indeed devastated, but most areas are only mildly singed. Undergrowth soon flourishes happily, and wildflowers are profuse in the following years. Wildlife doesn't seem to mind burned zones particularly. I even spent time in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness in the years immediately following the Biscuit Fire, possibly the nastiest burn in living memory. Even there, there are still living trees, limpid water, bears, salmon, carnivorous plants. The most dramatic aftereffects (in Idaho, at least) are landslides. The rivers have run clear much more seldom than they did before the fire years, as any reasonably focused downpour induces the loosened mountainsides to cast themselves down in a wall of mud, logs and stones, often giving the rivers some wonderful new rapids in the process.

Cramer Creek Rapid (a.k.a. De-Rig) formed overnight from a debris flow in August 2003, shortly after the Cramer Fire, creating some of the biggest whitewater on the Salmon.

Cramer Creek Rapid (a.k.a. De-Rig) formed overnight from a debris flow in August 2003, shortly after the Cramer Fire, creating some of the biggest whitewater on the Salmon.

My point in all this is that forest fires most definitely do not destroy an area's value as wilderness. Nature's change and growth is often not a gentle process; there is violence and destruction in it. That is where much of the awe and majesty of wilderness is to be found, and it is what sets true wilderness apart from gentlemen's estates. The notion implicit in salvage logging of burned forests is that the area is ruined, so why not pull what resources we can from it? I don't mind the resource extraction per se. What I greatly mind is the attendant road-building in roadless areas, excused on the grounds of this alleged ruination, which is believable only to those who have no serious knowledge of the areas. Wilderness should be managed as wilderness, through fires, floods and everything else. I say again, these areas are far from ruined, even on the scale of a few years. Seeing them change, through slow growth or sudden shock, in ways one would never guess, is one of the great delights and privileges of knowing the wilderness.

This is sadly likely to be an issue in my neck of the woods in the coming year. New Mexico has had no significant snowfall this season; our 12,000-foot mountains show no white at all. There have already been fires in Colorado: it's freakin' January! For all I've said above, please don't think I enjoy seeing forests burn. I definitely don't want to see the entire Pecos Wilderness burn in a week. If we don't get some precipitation soon, things will be very grim. But they'll still be better than an infestation of new roads.