"A bread pudding is not an alligator."Unfortunately, it was said by me. Context shall not be forthcoming. Happy New Year!

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Saturday, December 30, 2006

...Upon rereading, I suspect that the Germanic portion of my ancestry may influence me more than I had previously believed.

Two Subarus that won't be moving for a while.

Two Subarus that won't be moving for a while.

Last night, an acquaintance of ours from out of state reported being told, when the snow was only 14" deep, "I've never seen the like in twenty years." I can only conclude that the speaker was one of Santa Fe's many two-weeks-per-years residents; we are afflicted with a great infestation of these tourist homeowners. It's nonsense, of course: it did this two years ago, and heavy snows, though not common, are hardly unprecedented.

We're not going anywhere for a while, so maybe I'll come up with some more posts.

Sunday, December 24, 2006

To our amazement we learned that in valleys [in the Karakorum] where glaciers had disappeared, sometimes new, artificial glaciers are constructed by villagers. Glaciers are treasured in this dry country, for meltwater is the source of practically all irrigation. The last glacier to be started, we were told, had been made 35 years earlier by the grandfather of the present rajah. It had been built to an ancient formula, with ice blocks coming from male and female glaciers (their difference was not made clear). These blocks were deposited in a high valley and covered with charcoal and thorn bushes, on top of which 50 goatskins of water were placed. The water was to help keep the ice cool and to augment the ice supply when the water froze in winter. After 20 years of gradually adding ice and snow, the glacier became strong enough to support itself and send a constant supply of water in the nonwinter months to the dry fields below.From Robert H. Bates' account of the 1932 K2 expedition, told in The Love of Mountains is Best, pg. 119.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

The Peculiars will not be staying to enjoy Santa Fe's white Christmas, alas. We're off to, well, I'll just say it's where a lot of folks from my parts of the country got sent to die. If I'm lucky the trip will involve a prodigious great arroyo and a steakhouse depicted on The Simpsons. Best wishes to you, gentle readers, this festive season! We leave you with our take on a creche.

Let all of creation rejoice:

Finally, Mr. Armitage's shock and awe at the gralloching of a deer are comically professorial.

Sunday, December 17, 2006

Fine, I admit it, I finally broke down and went digital (Canon A540, if you're dying to know). I held out for a long time in the stubborn hope that I could muster the funds for a DSLR. But frankly, I could not have made the shot above (six-shot stitched pano) with my old film SLR, much as I love it. The new one is a lot of fun, and if I'd gotten it a year ago, I'd be about $300 ahead on processing costs. Farewell film: $300 buys a damn fine week or two shooting in the wilderness.

If I was having any twinges of buyers' remorse after ordering the new camera, it was gone when Mrs. Peculiar and I fortuitously watched Born Into Brothels. Looking at some of the shots these Indian street urchins produced with cheap point-and-shoots should put any gear-head photographer to deep, deep shame. (Here they are. Some are definitely better than others, but I'm seriously envious of a few.) Sure, I'd like a wider lens, but I have no right to gripe about any reasonably functional camera.

(Incidentally, it's well worth noting that Calcutta whorehouses seem to be a much better learning and growing environment than American suburbs and schools. These kids are far nicer, cheerier and smarter than 99% of American children; I'd invite them into my house. The movie doesn't preach about this, doesn't preach about much really, which I always fear in this kind of film. It's mostly just footage of a bunch of smart kids having fun with photography.)

Enough digression. I promise not to post every consarned gorgeous sunset that comes down the pike.

Saturday, December 16, 2006

I recently stumbled across a historical maniac quite new to me in this old John Derbyshire column:

The Seven 'Kill' Stele was erected by Zhang Xianzhong (pronounced "Jang Shee-en Jwoong"), one of the worst mass murderers in Chinese history, which is saying a very great deal...I read French, and if anyone knows of a copy, I'll take it in either language.First he killed all the educated people — always a strong temptation for the would-be Chinese despot, apparently, when megalomania begins to assert its grip. Zhang ordered all the literati of Sichuan to Chengdu, his capital, for a "special examination". Once they were there, he massacred them. Next he killed all the Buddhist clergy. Then he broadened his field of operations, and began killing at random. His intention seems to have been to exterminate the entire population of Sichuan, at that time probably around twenty million. He very nearly succeeded, if the oral tradition can be believed. Hu-Guang tian Sichuan, say local people with a shudder and a shake of the head: that is, there were so few people left alive in Sichuan after Zhang was through, the province had to be re-populated from the "Hu" and "Guang" provinces (Hunan, Hubei, Guangxi, Guangdong). When he ran out of people to kill, Zhang turned his fury on the inanimate world: he set his troops to pulling down buildings, broaching dykes and burning forests.

When news came that forward scouts of the Manchu armies had been spotted in the north of the province, Zhang gathered all his men together on a plain outside Chengdu. He made a speech to them along the following lines: "The great battle for the Empire is about to begin. I want you all to fight like true soldiers, with nothing on your minds save the thought of victory. To make sure you are not distracted or weakened by other concerns, I hereby order you to kill your womenfolk and your children." To give the example, Zhang thereupon turned, drew his sword, and slew his eight wives, who were standing by him. Thus inspired, his troops all butchered their own families, until the ground was soaked with the blood of these innocents. Zhang then rode out to meet the Manchus. Fortunately the Manchus were terrific archers, and a well-placed arrow ended the career of the "King of the West"...

At some point in his career of homicide, Zhang felt it necessary to explain himself to the world. He therefore caused a stele to be erected, inscribed with the following three lines of seven Chinese characters each: Tian sheng wan wu yi yang Ren, Ren wu yi shan wei bao Tian, Sha sha sha sha sha sha sha. Here is a translation (with, for a Chinese reader, an understood "but" between first and second lines, and a "therefore" between second and third):

That was the Seven 'Kill' Stele. It was still standing outside Chengdu well into the last century. Five or six years ago I asked a friend visiting the city to try to locate it for me. However, the local authorities told her it had been blown up by a PLA demolition squad sometime in the 1970s.

Heaven has brought fourth numberless things for the nourishment of Man.

Man does not do one good deed in recompense to Heaven.

Kill kill kill kill kill kill kill.It is a measure of the moral atmosphere of Chinese communism that this revolting psychopath, on account of his early land-to-the-peasants moves and his patriotic opposition to the Manchus, is rated as a "positive character" in communist history books — even, in one 1979 encyclopedia, a "hero of the common people".

N.B. Zhang had a Portuguese Jesuit in his entourage, who survived and wrote a book in French about his experiences. The School of Oriental and African Studies in London has a copy. Alas, I cannot read French. If anyone knows of an English translation, I should very much like to get a copy.

Anyway, I'm sure the books contents will be familiar to most people who have ever had much conversation with me. "More breeds than of dogs; uncanny homing abilities; remarkable long-distance races; champions selling for ridiculous sums; pigeons decorated war heroes." I wonder whether the author found out about the pigeon vendettas among Italian thief-pouter flyers. You've heard it all before. I certainly wish the author well, but it's always a little galling to be reminded how little expertise in a subject has to do with publishing a book on it. I could have written this book; Steve Bodio did write this book, quite some time ago. Sigh. So ist die Lauf der Welt.

I've added GOAT-A High Country News Blog to the sidebar. High Country News is a very fine source for updates of the state, whether laudable or deplorable, of the Rocky Mountain West. (Hat tip: Chas, of course.)

Friday, December 15, 2006

Hard on the heels of our moment of international repute, we have here more content you will not find elsewhere on the much-vaunted "World Wide Web." Below is I believe the only extant image of the entire Querencia pack, five tazis plus a lurcher and a wiener dog. Before last summer, the three big tazis represented 100% of the breeds Western Hemisphere population. Now, the five depicted represent approximately 40%, I'm happy to report.

Friday, December 08, 2006

Thursday, December 07, 2006

The folks at Querencia are always blogging rock art, so I was inspired to do the same when I found a couple long-forgotten photos in an old trunk. These pictographs represent a very obscure tribe, the Sheepeater Shoshone of central Idaho (also sometimes called the Tukudeka). Both of these small panels are found near the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, one of the deepest and wildest river canyons in the nation. They are probably painted with iron oxide pigment mixed with animal fat and blood. The bird and bighorn (below) seem clear enough, and the well-endowed gentleman is a common enough theme in the area. One excellent panel, unfortunately not shown here, is called by names which vary according to rafting company: Shark Fin, for the prudes, after a distinctive boulder in the river nearby; One-Hung-Low by my compatriots; Big Chief Long-Dong by the unapologetic.

There are plenty of things to say about the Sheepeaters. They were a Numic-speaking people (like other Shoshone, Paiutes, Bannock, Goshutes and Utes). Beginning around the 15th Century, the Numic speakers spread from somewhere around Southern California to fill Nevada, Utah, the southern half of Idaho, western Wyoming and western Colorado. These tribes shared closely-related languages and common lifestyles of hunting-gathering and seasonal migration up into historic times.

Dagger Falls: some rock art is present here, though very deteriorated. Salmon can still be observed leaping up the falls in season, and the fishing here must have been excellent in Sheepeater times.

The effects of the European arrival were felt in the American West long before any actual Europeans showed up. Most notably, the Spanish brought horses into New Mexico, which soon escaped and went feral, and were gathered or stolen by the locals and traded northward. By the late 1700s, they'd made it to the Northern Rockies, and local lifestyles changed dramatically as a result. Tribes such as the Nez Perce, the Shoshone and the Utes were suddenly able to cover distance and carry a lot; they therefore began making seasonal expeditions east to the plains to hunt buffalo. The Plains Tribes responded by raiding them (particularly the Blackfeet, who got guns from Canadian fur traders ahead of everyone else). These tribes from the western slopes of the Rockies thereby acquired many accoutrements of Plains culture, such as feathered headdresses and tipis (which they could now transport), and became generally more nomadic and combative of necessity.

These changes took root very near the Sheepeater country. In the Lehmi Valley, around the present-day town of Salmon, Idaho, the Lemhi Shoshone bred horses and made the short hop over the Continental Divide to chase buffalo. Every halfway educated American is dimly aware of this, for it was one such hunting expedition that got Sacajawea captured by Mandan and taken to North Dakota; and it was successful Lemhi horse breeding that allowed her brother Cameahwait to give some animals to Lewis and Clark in 1804.

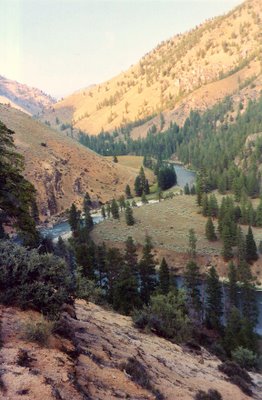

The Middle Fork country from high up: a small piece of river is visible lower right. The pink flowers are Bitterroots, endemic to eastern Idaho and western Montana, and an important food for local tribes.

While their Shoshone relatives in the broad valleys and plains of southern Idaho and Wyoming went along with this flow, the Idaho Sheepeaters are fascinating because they ignored these developments. Unlike the Lemhi Valley, Central Idaho just to the west is not good horse country; the Salmon River Mountains are a dense, incoherent knot of rugged peaks and very deep canyons. Furthermore, neither the river system nor the tribe was named at random: the biannual salmon migrations and the prolific bighorn sheep populations provided abundant resources for the Tukudeka. Though they continued their short seasonal migrations from high-elevation hunting grounds to low winter settlements, the Sheepeaters continued to winter in Northwestern-style pit-houses (there are many visible collections of house-pits on the Middle Fork), catch salmon and hunt sheep.

Typical river terraces where the Sheepeaters would build their house-pits. These were winter quarters with good exposures to sun and fairly low elevation. Much of the Middle Fork flows through a semi-desert environment, due to rain shadow effects of the surrounding mountains.

The few ethnographers who were aware of them at all long assumed that the Sheepeaters were degenerate hillbilly Shoshones, living a benighted existence in the mountains and evidently unable to find anything better to do. In fact, the Sheepeaters were known for excellent quality hides; they tanned one sheep's hide with two sheeps' brains, producing a valuable item that was traded for foreign commodities (notably obsidian; stone from both Yellowstone and the Cascades has been found in the area), and not a mark of abject poverty. Furthermore, there is no record of the Sheepeters eating grasshoppers, common practice among the Plains Shoshone and Bannock. Eating salmon instead of bugs is usually a sign that one is fairly well-off.

Sadly, the Indian Wars of the 1870s did not bypass this small and out-of-the-way tribe. 1876 was the year of the Little Big Horn; '77 saw the Nez Perce War; '78 the Bannock War in southern Idaho and eastern Oregon. In 1879, the Sheepeaters were one of the last unfought tribes in the Northwest. Unknown assailants killed a family of settlers near the South Fork of the Salmon, and some Chinese miners were murdered on the Yankee Fork, almost certainly by whites. It was easy to blame the Indians, and the merchants in Boise agitated for war. One wrote unabashadly in 1878 of eastern Oregon's "good fortune to have an Indian war and the concomitant shower of greenbacks all to itself."

Rough country for infantry: the army traversed a lot of this terrain, with mules, supplies and small artillery.

Two army columns were sent into the Salmon River Mountains, one from the south and one from the east. Their journals tell a rather farcical story of ten-foot-deep snowdrifts, blazing sun in the canyons, rattlesnakes, mules frequently tumbling down the slopes, but nary a sign of an Indian. Central Idaho is convoluted country, and the army was out of its depth. When one column at last met resistance on the slopes above Big Creek, the lieutenant promptly distinguished himself by hiding behind a tree. The soldiers were pinned down for over 36 hours and resorted to drinking vinegar (the site is named Vinegar Hill); the sound of Big Creek's cascades below must have been irritating in the extreme.

The Middle Fork near the confluence with Big Creek. The false summits in the photo are nowhere close to the top of the canyon, which rises 7,000 vertical feet in five horizontal miles from river to summits in this area.

At last, the army got lucky and captured a small group of women and children, along with one man, a Bannock refugee from the previous year's war. Desperate at this point to save face by returning from the mountains with a vaguely respectable number of Sheepeaters in tow, the lieutenant cut a deal with the Bannock. He led them to a Sheepeater camp, they rounded up the Indians and marched in dubious glory to Fort Hall in southeastern Idaho, still a Shoban (Shoshone-Bannock) reservation today.

There were undoubtably Sheepeaters remaining in the mountains after that summer, but the loss of even a small group was surely a major blow to so small and isolated a tribe. As we have seen above, they did rely at least somewhat on trade for their living, and there were no longer any free tribes nearby to trade with. What's more, central Idaho was declared open, and miners poured in. There is no direct record of what happened to the remaining Sheepeaters, but it seems safe to assume that they gradually headed south to the reservations. There they intermingled with plains Shoshone, Bannock and Northern Paiutes, and all intimate knowledge of the West's most isolated people, the tribe least changed by horses and guns, was lost.

The army named the lower reaches of the Middle Fork 'Impassible Canyon', but Shoshone pictographs are particularly abundant in these mazes of cliffs.

Source: The only book I know with a significant amount to say about the Sheepeaters is The Middle Fork: A Guide by Cort Conley. It includes extensive and often quite amusing excerpts from the soldiers' journals in the Sheepeater War. The Wikipedia entry on the Sheepeater War is laughably ill-informed. Particularly risible is this: "Sheepeater raiding party of ten to fifteen Indians attacked the troops as they rode on a train at Soldier Bar on Big Creek." The author is clearly thinking of a locomotive, but the only trains ever to have entered the Salmon River Mountains are equine, thank God!

(Final remark: the cohabitation of this post with Odious' charming tipi photograph is purest coincidence.)

All photographs are my own.

Monday, December 04, 2006

Via The Athanasius Kircher Society, which has been having a wonderful language week.

Friday, December 01, 2006

To quote the immortal film Conan the Barbarian, "Five years ago, it was just another snake cult."

Buried beneath utterly dreary headlines about Oldest Form of Worship and suchlike is this story: "An archaeologist claims to have found evidence of what may have been mankind’s earliest rituals: worship of the python, 70,000 years ago in Africa." The most sober and informative article I've found is here. Located in San (Bushman) territory in Bostwana, the site features what is allegedly a stone "carved to enhance its resemblence to a snake." Unfortunately the photographs are insufficient to judge for oneself, for me at least. What's more,

Hundreds of small notches, widely spaced in some places and closer together in others, covered the rock. Entrants to the cave apparently made these markings to enhance the snake illusion by creating the impression of scales and movement. "When flickering light hits it, it very much looks like the snake is flexing," Coulson says.An aspect of rock art you don't hear much about is the carving of stones to enhance their resemblance to something. I recall that such was the exegesis of one stone in Fremont Indian State Park in Utah: it had had a few marks added to make it look like a bird with its head tucked beneath a wing.San mythology holds that mankind descended from the python. Ancient, arid streambeds around the hills are said to have been made by the snake as it circled, ceaselessly seeking water.

More rock art coming.